The dorm meeting was nothing out of the ordinary.

What happened during the meeting was anything but ordinary.

Jon attended a public university studying toward a degree in business. His resident adviser (RA) had called a floor meeting. Jon, a freshman, showed up early. He and his RA began a casual discussion.

Jon attended a public university studying toward a degree in business. His resident adviser (RA) had called a floor meeting. Jon, a freshman, showed up early. He and his RA began a casual discussion.

Soon the chat turned toward the question of “What is real?” The RA was a Hindu, Jon, a Christian. Jon had learned that the best way to determine someone’s point of view was simply to ask questions. The RA’s offerings to the conversation were met with more, deeper questions.

The two men continued in dialogue as the floor meeting room began to fill with other students. Jon was not antagonistic, overbearing, or argumentative. He simply asked questions. The Hindu became more and more frustrated, not so much by the questions, but because he was unable to answer them. Finally, in exasperation, the RA left the room.

The two men continued in dialogue as the floor meeting room began to fill with other students. Jon was not antagonistic, overbearing, or argumentative. He simply asked questions. The Hindu became more and more frustrated, not so much by the questions, but because he was unable to answer them. Finally, in exasperation, the RA left the room.

The room was full of students from the dorm floor. It was the time for the scheduled meeting.

The students had been quietly listening to the discussion. The RA’s departure left Jon standing in the middle of the room, alone.

The students had been quietly listening to the discussion. The RA’s departure left Jon standing in the middle of the room, alone.

And then a voice from the back asked, “So how would you answer your own questions?”

Jon was not caught off guard. He began to explain his Christian beliefs.

His senior year in high school Jon had been in my class. We discussed questions such as “What is real?” The method of investigation was always one of questioning. Our approach was winsome, kind, generous, learning how to shower others with grace. Apologetics (defense of The Faith) was directed toward attraction rather than confrontation. Examples of appealing dialogues between Christians and non-Christians were explored.

His senior year in high school Jon had been in my class. We discussed questions such as “What is real?” The method of investigation was always one of questioning. Our approach was winsome, kind, generous, learning how to shower others with grace. Apologetics (defense of The Faith) was directed toward attraction rather than confrontation. Examples of appealing dialogues between Christians and non-Christians were explored.

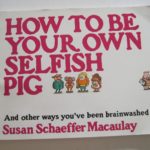

How to Be Your Own Selfish Pig helped connect students with other points of view. The only book I ever used as a text outside of The Bible in my classes in the 1990’s was Susan Schaeffer Macaulay’s book. Susan, Francis Schaeffer’s daughter, presented her father’s seminal teachings in story form. “The Hindu and the Teakettle” is a narrative from the book my students never forgot. Susan tells the story this way:

How to Be Your Own Selfish Pig helped connect students with other points of view. The only book I ever used as a text outside of The Bible in my classes in the 1990’s was Susan Schaeffer Macaulay’s book. Susan, Francis Schaeffer’s daughter, presented her father’s seminal teachings in story form. “The Hindu and the Teakettle” is a narrative from the book my students never forgot. Susan tells the story this way:

One afternoon, my parents visited Cambridge University, and met with some students in the living room of a college apartment. My husband-to-be, Ranald, his good friend Tom, and other students gathered around the fireplace. A teakettle was whistling cheerfully on a gas burner nearby, promising hot cups of tea.

As the group discussed ideas, one young man from India, who was Hindu by religion, started to speak out against Christian ideas of truth. My father decided to probe this fellow’s own conclusions, to show that he could not actually live and act upon what he said he believed.

“Are we agreed,” my father asked, “that you believe there is only one reality, which includes all things, all ideas?”

The young man nodded.

“Then,” my father pursued, “this means that, ultimately, everything is the same. Any difference we see is temporary, an illusion. There is no such thing as a separate personality, correct? No final difference between good and evil, or between cruelty and non-cruelty?” The young man agreed again, but the others in the room were surprised at what the full extent of their friend’s Hindu beliefs could be.

Tom was struck with the fact that such beliefs didn’t fit into the real world. But instead of arguing, he reached for the steaming teakettle, lifted it off the gas burner, and held it over the startled Indian’s head. Everyone looked surprised, and the Indian student looked scared to death.

“If what you believe is really true,” Tom said firmly, “there is no ultimate difference between cruelty and non-cruelty. So whether I choose to pour this boiling water over your head or not doesn’t really matter.”

There was a moment of silence, and then the Indian rose and left the room without comment. He could not match what he believed with real life. [1]

When Jon’s RA left the room, Jon knew what to say. He had learned how to speak with others holding divergent beliefs. He knew what he believed. More importantly, Jon knew how to communicate why he believed what he believed.

And Jon’s dorm mates knew what he believed too.

Jon’s story could be replayed over and over by many students. May their lives and lips continue to attract others to The Faith. Dr. Mark Eckel is president of The Comenius Institute.

[1] Susan Schaeffer Macaulay, “The Hindu and the Teakettle,” How to be Your Own Selfish Pig, Chariot Books, 1982, pp. 28-29.