It is difficult to hide one’s tears on a plane.

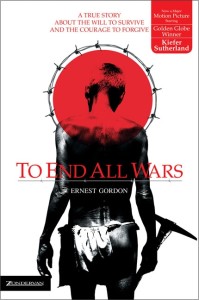

The flight was Chicago to Los Angeles. My in-flight reading was To End All Wars. Ernest Gordon writes about his three year experience in a Japanese prisoner of war camp during World War II.

I was moved to tears.

Gordon recounts what anyone would expect: awful physical conditions, beatings, executions, undernourishment, disease, and the ever-present desire for hope. Gordon was not a Christian when imprisoned. By his own admission, Gordon’s personal belief mirrored

Gordon recounts what anyone would expect: awful physical conditions, beatings, executions, undernourishment, disease, and the ever-present desire for hope. Gordon was not a Christian when imprisoned. By his own admission, Gordon’s personal belief mirrored

Matthew Arnold who said we are on earth “as on a darkling plain”, doomed by the processes of nature to begin to die as soon as we are born. [1]

Gordon’s response? “Isn’t that what we have to face?”

Ernest Gordon had been raised within a naturalistic view of life. Gordon’s sociology was his theology. As he says

“The rapid progress being made in [the sciences] indicated that man could take care of himself and unravel his own

dilemma without help from a divine power, no matter how benign. Of such was the real world in which man had been placed by the evolutionary process, as the one creature conscious of what was going on. As he floated down the stream of history, he could know that the current would ultimately land him in Utopia. Many brave worlds were being projected in those days, and mine was one of them.” [2]

When confronted by a prison camp, however, Gordon adds, “We had no idea how soon those brave new worlds would  prove to be mirages.” [2]

prove to be mirages.” [2]

A change of heart began, however, with a simple giving of bread. It seems there were a few Christians in the camp. One believer gave up his meager meal to another prisoner. Gordon tells how the small gift turned into a large transformation:

“Our regeneration, sparked by conspicuous acts of self-sacrifice, had begun . . . It was dawning on us all—officers and other ranks alike—that the law of the jungle is not the law for man. We had seen for ourselves how quickly it could strip most of us of our humanity and reduce us to levels lower than the beasts. We were seeing for ourselves the sharp contrast between the forces that made for life and those that made for death . . . Through our readings and discussions we gradually came to know Jesus. He was one of us. He would understand our problems, because they were the kind of problems he had faced himself.” [3]

Theology was now driving sociology.

Theology was now driving sociology.

Gordon knows many believe “There’s nothing to life beyond the fact that we are born, we suffer and we die.” He continues

“Most of us were accustomed to such an answer, for it had been stamped indelibly on our subconscious minds by the many conditioning processes of the twentieth century. If I had learned to trust Jesus at all, I had to trust him here. Reason said, “We live to die.” Jesus said, “I am the resurrection and the life.” [3]

Jesus changed a prison camp culture. So, theology should drive one’s sociology.

Jesus changed a prison camp culture. So, theology should drive one’s sociology.

Gordon’s life lesson is exactly reflected in Robert Woodberry’s research. Woodberry’s decade-long work investigated the impact of “conversionary Protestant” 19th century missionaries with the people to whom the gospel message was delivered. Cultural transformation–the health of neighborhoods, cities, nations–begins with a change of heart through faith in Jesus as Savior from sin. [4]

Living a good life is not enough.

A good life is premised upon God’s good gift of salvation (see Mark’s Theo “Sanctification”).

People cannot be “saved” from their circumstances by good works.

Christian theology must drive Christian sociology.

Good works without the saving work of Christ is empty.

Ernest Gordon’s book will bring tears to your eyes.

Jesus’ work in his life will prompt goodness with your hands.

————————–

Mark has written earlier about Gordon in “Ice Axe to the Frozen Sea,” an essay included in his latest book I Just Need Time to Think! Dr. Mark Eckel emphasizes to his students at Capital Seminary, The Master’s Study, and everywhere else he teaches that our theology should drive our sociology.

[1], [2] Ernest Gordon, To End All Wars, p. 115.

[3] Ibid. pp. 103, 105, 107, 117, 119.

[4] Andrea Palpant Dilley, “The World the Missionaries Made,” Christianity Today, Jan/Feb, 2014, 34-41.

The movie came up as an example of Christian vision in practice at a training seminar two Mondays ago. I have met the screen-writer because I taught his niece in her 5th grade. I was struck at the time I first saw it by the powerful presentation of grace in the face of sin. There are few directors who are making movies where the contrast of grace with depravity is really shown. I have also been challenged by movies that show the enticing elements of sin, but ten they show you the unraveling of life from its shalom purpose as sin works out its effects.

Thank you for connecting the movie with the social sciences. I look forward to having you teach my class in April.

“Christian theology must drive Christian sociology”

This is a point in itself worth writings. Too often I find that Christians “proof text” their approach to sociological issues. I will have to add this book title to the reading list. Thanks for your thoughts.

I would appreciate any further texts you could mention on theology as the driver to other theoretical study areas. Specifically, I’d like to formulate an interdisciplinary approach based on theology to look at identity formation and cultural/social identity. With theology as the base instead of a category of values in the development of identity.