He was stuck on a boat, returning from a European trip. For eight days, all he could hear were the ship’s engines going, chug-chug-chug. It seems the sound got stuck in his head. From that moment on, Theodor Geisel began to write books according to rhythm. Rhythm turned to rhyme in his first children’s book entitled And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. An Atlantic Ocean crossing and the chug-chug-chug of those engines began the career of the man who could tell children’s stories in poetry. Of course, Theodor Geisel is better known as Dr. Seuss.

Seuss’s first book And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street turned 75 this year. Originally, publishers rejected the book 27 times. As one historian tells it, Geisel had almost given up on the book, deciding to destroy it instead. But a surreptitious encounter with an editor friend as he walked home one evening after work changed all that. Had Geisel been walking on the other side of the street we might never know of Dr. Seuss. The editor friend liked Mulberry Street, got it published, the book received great reviews, and for six decades after, everyone knew the name Dr. Seuss.

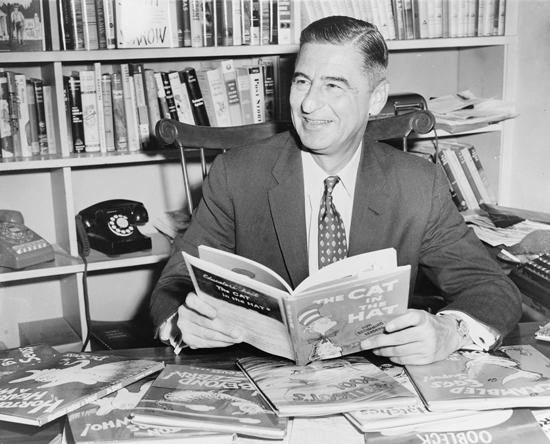

Seuss’s brilliant way with words was wonderfully augmented by his own artwork. Verbal and visual came together in Dr. Seuss books to tell story in poetry. As with any writer, Dr. Seuss also stirred controversy with his political viewpoints. The Lorax was Geisel’s environmental treatise against the business of cutting down trees. And The Butter Battle Book was Geisel’s view of The Cold War. Seuss wrongly believed the only moral difference between Communist Russia and Western democracy was the difference between choosing to butter a slice of bread on the top or bottom. However, many stories were morality tales I have used to teach positive lessons. Yertle the Turtle explains that some leaders get too big for their britches, ending up in ditches. How the Grinch Stole Christmas pronounces one’s view of holidays depends on the size of one’s heart. My personal favorite, Horton Hears a Who, contains the line which preaches by itself: “a person’s a person, no matter how small.”

Students from junior high to graduate school have heard me read Dr. Seuss both in disagreement and in celebration. Teachers have used Theodor Geisel’s rhythm and rhyme books to coach phonics. Green Eggs and Ham or The Cat in the Hat are titles which have taught children to read. The chug-chug-chug of a ship’s engines changed the course of children’s publishing. I own every Dr. Seuss book in print. The reason? I could never preach in 45 minutes what Dr. Seuss books help me teach in 5. For Moody Radio, this is Dr. Mark Eckel, personally seeking truth wherever it’s found.

Poetry in story, Mark believes, is the best communication combination. This post will air on Moody Radio sometime April-June 2012.