The Old Testament is not “old,” it is First.

The First Testament was written to the first group of God’s People, Israel.

One Book was written by One author with one message. The English reader tends to see the Bible as a series of books rather than the meaning of Bible: The Book. Compartmentalizing books within the canon makes the 21st century Christian miss the continuation of God’s story begun in Genesis, consummated in Revelation. Understanding the coherence of God’s revelation to His people is crucial. Just as threads—small fibers or strands—unite to produce one, strong length of rope, so Scripture’s purpose is captured in many themes throughout The Book.

One Book was written by One author with one message. The English reader tends to see the Bible as a series of books rather than the meaning of Bible: The Book. Compartmentalizing books within the canon makes the 21st century Christian miss the continuation of God’s story begun in Genesis, consummated in Revelation. Understanding the coherence of God’s revelation to His people is crucial. Just as threads—small fibers or strands—unite to produce one, strong length of rope, so Scripture’s purpose is captured in many themes throughout The Book.

Biblical Theology of the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament

The author of the Bible is God. The unity of the Bible is held together by its Author. Throughout biblical history, God has established a complete view of Himself through His words and works. When the Christian reads the Bible she can then be assured the Author has given a whole, total, systemic view of what He wants His people to know (Rom 4:24; 1 Cor 9:10).

The author of the Bible is God. The unity of the Bible is held together by its Author. Throughout biblical history, God has established a complete view of Himself through His words and works. When the Christian reads the Bible she can then be assured the Author has given a whole, total, systemic view of what He wants His people to know (Rom 4:24; 1 Cor 9:10).

The scope of the Bible is broad, capturing the bird’s eye view of God’s eternal plan. Individuals from nations fulfill a universal perspective. Joseph, for instance, is the person who is used to save Israel from starvation, while Israel is used to save the world through Messiah (Gen 50:20). Ruth’s foreign status serves a worldwide purpose: the Davidic dynasty (Ruth 4:13-18). David is Israel’s great king whose lineage births The King of kings (Matt 1:1).

The scope of the Bible is broad, capturing the bird’s eye view of God’s eternal plan. Individuals from nations fulfill a universal perspective. Joseph, for instance, is the person who is used to save Israel from starvation, while Israel is used to save the world through Messiah (Gen 50:20). Ruth’s foreign status serves a worldwide purpose: the Davidic dynasty (Ruth 4:13-18). David is Israel’s great king whose lineage births The King of kings (Matt 1:1).

Theological connections begun in the Old Testament continue through to the New Testament. God’s sovereignty and human responsibility are both shown as true, though the explanation is difficult. Exodus, for example, notes God “hardened pharaoh’s heart” (7:3, 13, 14, 22; 8:11, 15, 22; 9:7, 34) while “pharaoh hardened his heart” (9:12; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:10; 14:4, 8, 17). Humans continue to bear responsibility for their own actions while at the same time God superintends all things (Acts 2:23).

Theological connections begun in the Old Testament continue through to the New Testament. God’s sovereignty and human responsibility are both shown as true, though the explanation is difficult. Exodus, for example, notes God “hardened pharaoh’s heart” (7:3, 13, 14, 22; 8:11, 15, 22; 9:7, 34) while “pharaoh hardened his heart” (9:12; 10:1, 20, 27; 11:10; 14:4, 8, 17). Humans continue to bear responsibility for their own actions while at the same time God superintends all things (Acts 2:23).

The synthesis of the Bible serves to encourage everyone within their time to anticipate God’s ending of time (Rom 15:4; 1 Co. 10:1-11). Scripture constantly foresees those who would follow (1 Pet 1:10-12). The nature of the Old Testament is to point forward to the New Testament. The seed of sin sown in Genesis is uprooted in The Gospels. Jesus teaching about Himself throughout God’s testament to the Hebrews is explained in His testament to Christians (Luke 24:25-27). Passages such as 1 Peter 2:9-10; Revelation 1:5-6 and 5:10 never lose God’s missional purpose.

The synthesis of the Bible serves to encourage everyone within their time to anticipate God’s ending of time (Rom 15:4; 1 Co. 10:1-11). Scripture constantly foresees those who would follow (1 Pet 1:10-12). The nature of the Old Testament is to point forward to the New Testament. The seed of sin sown in Genesis is uprooted in The Gospels. Jesus teaching about Himself throughout God’s testament to the Hebrews is explained in His testament to Christians (Luke 24:25-27). Passages such as 1 Peter 2:9-10; Revelation 1:5-6 and 5:10 never lose God’s missional purpose.

Christian Practice for the Hebrew Bible

A general overview should precede the teaching of any biblical text. The use of charts helps the parts of a passage become whole. Diagrams can create simple insights from a complex narrative. Images from ancient archaeology or geography can focus a learner’s awareness of detail. The big picture observation of a text prior to teaching can lead learners to detailed interpretation and ultimately personal application. A Bible encyclopedia search shows that the ten plagues against Egypt functioned as God’s victory against other gods (Deut 12:12; 26:5-9; Josh 24:12-13) explained well with a visual aid.

A general overview should precede the teaching of any biblical text. The use of charts helps the parts of a passage become whole. Diagrams can create simple insights from a complex narrative. Images from ancient archaeology or geography can focus a learner’s awareness of detail. The big picture observation of a text prior to teaching can lead learners to detailed interpretation and ultimately personal application. A Bible encyclopedia search shows that the ten plagues against Egypt functioned as God’s victory against other gods (Deut 12:12; 26:5-9; Josh 24:12-13) explained well with a visual aid.

Interconnecting ideas beginning in the Old Testament should be traced. Connections to multiple concerns of apologetics, doctrine, history, or biography can bring the whole focus of Scripture into clarity. Correlation—finding how passages fit together from across the Bible’s pages—reminds the reader of Scripture’s scope. Finding God’s Hebrew name in Exodus 3 is translated as “I am” makes sense to the learner when they find out the simple phrase was used by ancient kings as a marker of their ultimate status and is used by Jesus to show He is the Hebrew God (John 8, 10, 18)

Interconnecting ideas beginning in the Old Testament should be traced. Connections to multiple concerns of apologetics, doctrine, history, or biography can bring the whole focus of Scripture into clarity. Correlation—finding how passages fit together from across the Bible’s pages—reminds the reader of Scripture’s scope. Finding God’s Hebrew name in Exodus 3 is translated as “I am” makes sense to the learner when they find out the simple phrase was used by ancient kings as a marker of their ultimate status and is used by Jesus to show He is the Hebrew God (John 8, 10, 18)

Teaching large sections of Scripture lends itself to a big picture view. Themes from one part of a book to another can add to understanding. The word “serve” in Exodus, for instance, is the same word for “worship” appearing scores of times in Exodus as “service,” “serving,” or “servant.” Moses is called God’s servant almost fifty times; the term was used by ancient Near Eastern kings for themselves, working on behalf of the deity (Josh. 1:2).The book begins by Israel serving an Egyptian pharaoh, God taking His people out of Egypt to serve Him, and ends with the building of the tabernacle: the place of Israel’s service-worship.

Teaching large sections of Scripture lends itself to a big picture view. Themes from one part of a book to another can add to understanding. The word “serve” in Exodus, for instance, is the same word for “worship” appearing scores of times in Exodus as “service,” “serving,” or “servant.” Moses is called God’s servant almost fifty times; the term was used by ancient Near Eastern kings for themselves, working on behalf of the deity (Josh. 1:2).The book begins by Israel serving an Egyptian pharaoh, God taking His people out of Egypt to serve Him, and ends with the building of the tabernacle: the place of Israel’s service-worship.

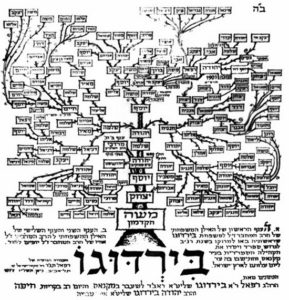

Genealogical teaching begins in Genesis (chapters 4, 5, 10, 11, 25, 36, 49) and is bracketed by the final Old Testament book, Chronicles (chapters 1-9). To understand Jesus’ genealogies of Matthew 1 and Luke 3, the Christian must see the links beginning in Genesis 4 to Genesis 49 to Ruth 4 to Romans 1:2-4. Hebrew thinking about people in Scripture is directly tied to ancestry.

Genealogical teaching begins in Genesis (chapters 4, 5, 10, 11, 25, 36, 49) and is bracketed by the final Old Testament book, Chronicles (chapters 1-9). To understand Jesus’ genealogies of Matthew 1 and Luke 3, the Christian must see the links beginning in Genesis 4 to Genesis 49 to Ruth 4 to Romans 1:2-4. Hebrew thinking about people in Scripture is directly tied to ancestry.

Simple teaching is the most powerful teaching and can be benefited by mnemonic devices. Laying out Old Testament geography on a classroom floor comes to life when participants hold up a red-C for The Red Sea or pass out caramels at Mt. Carmel. The book of Leviticus can be taught with the poem “Sacrifices, priests / Special days, feasts / Law code, disease / You can’t do what you please.”

Christian teaching should always lead to application from the Old Testament. Israel “trembled with fear,” is told not to fear, and yet to fear God (Ex. 20:18-20). How can people be afraid while being told not to fear, yet, to fear God? It seems people cannot live with God and cannot live without Him either. Jesus’ disciples first showed fear and then refocused their fear when Jesus calmed the storm (Mark 4:35-41). Peter’s response to Jesus’ knowledge of fish schools was a fearful desire to be out of His presence (Luke 5:1-11). Ultimately Christian fear (Phil 2:14-15) should be mindful of adoration that comes from knowing Whom to fear: what Job knew, Paul knew too (Job 42:1-6; Rom 11:33-36).

Christian teaching should always lead to application from the Old Testament. Israel “trembled with fear,” is told not to fear, and yet to fear God (Ex. 20:18-20). How can people be afraid while being told not to fear, yet, to fear God? It seems people cannot live with God and cannot live without Him either. Jesus’ disciples first showed fear and then refocused their fear when Jesus calmed the storm (Mark 4:35-41). Peter’s response to Jesus’ knowledge of fish schools was a fearful desire to be out of His presence (Luke 5:1-11). Ultimately Christian fear (Phil 2:14-15) should be mindful of adoration that comes from knowing Whom to fear: what Job knew, Paul knew too (Job 42:1-6; Rom 11:33-36).

“Hebrew Bible and Old Testament” © is one of 17 articles included in The Encyclopedia of Christian Education, Rowman & Littlefield, April, 2015 by Dr. Mark Eckel.

“Hebrew Bible and Old Testament” © is one of 17 articles included in The Encyclopedia of Christian Education, Rowman & Littlefield, April, 2015 by Dr. Mark Eckel.

Dr. Mark Eckel is President of The Comenius Institute (website), spends time with Christian young people in public university (1 minute video), hosts a weekly radio program with diverse groups of guests (1 minute video), interprets culture from a Christian vantage point (1 minute video), and teaches weekly at his church (video).

Help Comenius reach its $40,000 giving goal before the new year! The Comenius Institute [501(c)(3)] (website here) Donate online (here), mark@comeniusinstitute.org, (text/talk 630.303.4891) Checks to “The Comenius Institute,” c/o Collaborate 317, 4202 N EMS Blvd #180, Greenfield, IN 46140 And ask Mark what Comenius would do with $1 million!

Other Helps Gordon D. Fee and Douglas Stuart, How to Read the Bible for All It’s Worth, 3rd ed. (Grand Rapids, Zondervan, 2003). The English Standard Version Study Bible (Wheaton, IL, Crossway, 2008). Picture credit: SnappyGoat.com