Sometimes our choices

are a reparation for the past.

It begins with a decision at a traffic light.

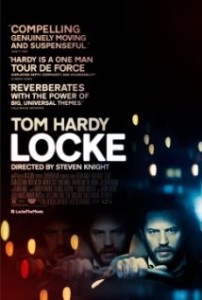

Truck horn blaring behind him, the light is green, his car blinker is set to turn left. In a sudden reversal, the dashboard arrow changes direction as does his life. Locke is a movie which will make everyone think twice before deciding which way to turn on the road of life.

Tom Hardy (“Bane” in The Dark Knight Rises) plays Ivan Locke, the only actor we see on screen. But there are two men present in the car. Locke makes a life-altering, job-abandoning, stability-destroying, marriage-ending moral choice, borne from how he was born. Locke has a running, one-sided tirade against his own father, absent but ever present. Locke is so injured, so embarrassed, so changed by his own bastard birth that he refuses to let it happen again. The decision many would make to cover up and cover over their own trespass is a decision Locke cannot make. Yet his choice on behalf of one, wrecks the lives of others. The choice is not made out of love or sentimentality. The choice is not made for greener pastures. The choice is not made out of spite, lust, or hatred. The choice is made as a reparation for the past.

Locke is a movie which turns upside-down the notion that our decisions in the present are always for a better future. The twisted threads of our own thinking are often woven on the loom of our past. Locke’s psychological pain has been written on his soul, now etched on the screen for us all to see. Locke is a “decent man,” “moral man,” “good man,” “the best man in England”—descriptors given by every one who knows him. He has treated others well. But Locke’s even-keeled nature has been swept along by an unseen current. Locke turns the rudder of his ship into the storm of agony from the anguish which has carried him this far.

It is no surprise that Locke works in concrete, the most temperamental of all building materials; something so fluid soon becomes set in stone, immovable. Now others will need to chip away the footprints he leaves behind. “Concrete footprints” and other indelible metaphors are written for the screen by Steven Knight, leaving permanent marks on our thinking. Knight is known for a wide range of scripts including Closed Circuit, Redemption, Dirty Pretty Things, and, perhaps, most surprisingly, Amazing Grace. His characters are given depth not always present in thinly drawn Hollywood performances. Tom Hardy’s superb acting is set up by Steven Knight’s skillful writing.

Tom Hardy’s brilliant portrayal of moral conviction is unlike any other I have witnessed. Life choices and decisions of character will be viewed in a different light after seeing Locke. We movie watchers will observe nothing more than a man, a car, and a road. But we are made to see that turn signals don’t always tell us where we’re going, but where we’ve been.

Rated R for language.

Mark believes with P. T. Anderson “we may be done with the past, but the past is not done with us” (Magnolia). Dr. Mark Eckel teaches the necessity of redemption through the cross of Jesus for our past sin giving us eternal life. Mark teaches these and other concepts at Capital Seminary & Graduate School, Washington, D.C. He lives in Indianapolis.