Chelsea’s face lit up as I took the book from my bag.

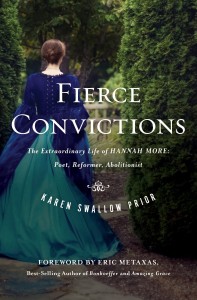

“I’ve been wanting to read about Hannah More!” she exclaimed.

“It’s yours after I finish the review,” I smiled.

You see, my daughter is much like Hannah; a legacy I hope her daughter will continue.

It is More’s moral imagination where I first saw my daughter’s face. Lover of novels and poetry, Chelsea and Hannah are cut from the same cloth, threads woven with the loving skill of Karen Swallow Prior’s Fierce Convictions.

The use of moral imagination was Hannah More’s greatest gift to the human race. Cultural transformation takes many forms. In More’s case a writer moved peoples’ minds helping to shape her world. Prior starts the projector allowing life to move effortlessly across the screens of our minds.

It is testimony to any writer that she can both lure an audience and secure her study. Prior’s research is impeccable. Footnotes alone (45 pages!) indicate the depth and breadth of investigation. Early on Prior sets Hannah’s historical record straight, ironing out what had been thought, discovering what is true. Parental heritage and impact is reinstated. Hannah found herself the beneficiary of a rags-to-riches background. Life may imitate art but in Hannah’s case

More’s life shows that the facts and our wishes can produce great stories when serving things much grander than ourselves, and that the stories we tell ourselves and others matter. This is the power of the moral imagination (13).

Stories impact one’s interiority, “engaging the whole heart” (221), the awakening of what evangelical Christianity was called in Victorian England: “religion of the heart.” Over and over Prior makes the point that moral imagination is crucial to understanding both Hannah’s personal growth and cultural goodness (121, 128, 134, 138, 187, 221-36).

Constant gardening, tending to what is good in a culture, is necessary because the weeds of evil are everywhere. In Hannah’s case, the greatest evil she battled was slavery. Slavery—every issue of injustice—is combated by many whose gifts are utilized for the cause. More wrote newspaper satires and church hymns to communicate the obvious: slavery was immoral and needed to end.

Today what is remembered and counted greatest among the accomplishments of the Clapham community is the abolition of the slave trade, but such a victory would likely not have been won without the groups’ successful attempts at reformation of the entire society, from high to low, from Sabbath to Saturday. The efforts of the Clapham community were three-pronged: they aimed at alleviating the suffering and oppression of the lower classes, reforming the excessive and negligent behaviors of the upper classes, and advancing Christianity at home and throughout the world. (173-74).

Transformation of one’s culture occurs over time through the auspices of moral imagination building a moral formation. To Hannah More and her sisters, the best type of formation was education. More upended the educational environment of the day focusing on story so that students could ponder applications to life. Reflection led to learning as virtue. Hannah and her “Bluestocking Circle” lobbed a stone into the still waters of English education making ripples which continue to wash ashore today.

Schools increased “the numbers of both young and old scholars” (149). Learning created learning cultures. Sunday schools and women’s clubs multiplied from one to sixty within a short time (152). The sisters’ work focused on creative instruction toward the needs of students resulting in “useful, productive citizenry” (157). More’s writing for the theatre and penning a novel showed cultural engagement essential to the Christian message if cultural redemption through Christ was possible. Teaching a nation to read, More concluded, “I know of no way of teaching morals but by infusing principles of Christianity, nor of teaching Christianity without a thorough knowledge of Scripture” (160).

Many literary friends—Christian and not—cheered Hannah and her work. More’s connection with John Newton and William Wilberforce would link her with cultural change agents from whom she learned, and for whom she benefited. Friendships place their mark upon us. And those whose voice would cause us encouragement are remembered with gratitude. A pleasant, broadening perspective for the reader are many incidental connections to other leaders and writers of More’s day. She seems to have had friends in every strata of society.

Hannah More was an anticipatory leader, one who sees the future, points it out, while leading the way. Prior’s assertion (108) that people could not “see slavery for what it was” is neither castigation nor acceptance of slavery’s appalling atrocity. One must always consider history within its context. Nonetheless, Hannah saw the awfulness, the repugnance of slavery setting out to right the wrong through her pen. A word of caution about Karen Swallow Prior’s inclusions about slavery: they are barely readable. There were times when I had to put the book down, such was the power of Prior’s horrific descriptions. The violent episodic slavery stories at once cause revulsion, then righteous indignation.

Prior follows the intersections of history yielding brilliant insights. For example, while Hannah was deeply benefited by Wesley’s preaching she did not subscribe to pietism’s platitudes, retreating from public life. On the contrary, More’s life was a beacon of light in the cultural darkness of her day. Yet Prior does not whitewash Hannah More. Stains periodically appear showing More to be one of us, a sanctified, sullied sinner.

The greatest compliment one can pay to a biographer is that the historical personage came alive in our reading. To me, Hannah More is now my friend. At times, we esteem some historical figures while neglecting others, the latter’s contributions seen only after some time. One senses in Prior’s writing a wellspring of gratitude for her predecessor. Karen Swallow Prior’s Fierce Convictions reminds us of the need for strong women in every generation.

The book will now be in the hands of my poet-daughter, her own fierce convictions helping to transform her own community. Hannah More would smile.

Dr. Mark Eckel prompts his culture and his classes of the need for strong Christian female leadership while teaching for Capital Seminary & Graduate School.