When adults surrender their role, children rule.

Children are incapable of being adults unless the adults abdicate their responsibility. The first-time writer (Gustin Nash) and first-time director (Jon Poll) of Charlie Bartlett would have us believe that a child’s problems can only be addressed by the children themselves.

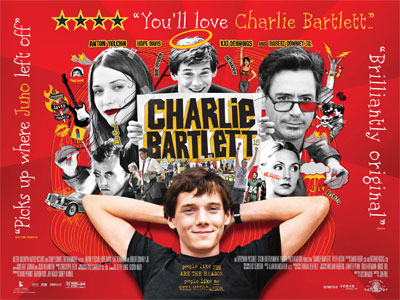

The “children-as-adults” perspective is easy to display on screen when all the prominent adults are acting like children themselves. Robert Downey Jr. plays the soused principal who bears all the marks of a self-obsessed individual rather than an educator and father. Charlie’s mother (Hope Davis) is infantile. The viewer never fully understands why a mom would behave as she does; she too belongs in the playpen, having her “parent card” revoked.

What has come to be accepted as “the norm” in our culture, mirrored in Charlie Bartlett, is that children are wiser, more mature than their forebears. Charlie (Anton Yelchin) has been expelled from every private school his rich family can afford. Left with the option of public education, Charlie must now try to garner popularity from another new group, because, as he says in an unusual fit of discomfort, “What else is there to gain from high school?”

The lack of a father in the home may be an underlying reason for Charlie’s actions. Dad is in prison on tax evasion; Charlie has been left without male guidance. Whatever the desire for Charlie’s want of people to like him—driven home in the very first scene where we see Charlie’s deep longing for acceptance.

Charlie is accepted by becoming the school shrink. Having his own psychiatrist on call and knowing the teenage problems foisted upon him, in of all places the boy’s bathroom, he begins to peddle drugs and advice. Popularity for Charlie is an overnight sensation when the student body at his high school becomes strung out on Ritalin.

Perhaps it began with James Dean in Rebel Without a Cause, but we have seen Charlie over and over again in docu-mockeries of out-of-touch adults in a teenage world: evidence Ferris Bueller’s Day Off or Rushmore as patterns followed here.

- Do teenagers have problems? Well, who doesn’t?!

- Does psychiatry deserve a stick in the eye for its elevated stature in our society? Well, duh!!

- Do adults merit a spearing for their inattentive, blithe acceptance of childhood behavior? Well, obviously!

The first half of Charlie Bartlett is the movie’s strength. A good story is told simply by telling the story. The last half of the film, however, descends into discontented preachments (through Kat Dennings, playing Susan, Charlie’s love interest and principal’s daughter), triumphant songs of individualism (Cat Steven’s, a.k.a. Yusuf Islam, “If You Want to Sing Out, Sing Out”), and an overthrow of the adult world by victorious, childish teenage hysteria.

Watch the first 45 minutes of Charlie Bartlett for a laugh-out-loud skewering of all the powers that be. Even the teenagers are shown with foibles. If Nash and Poll had stopped there, the film would have been a success, pointing out all of our inconsistencies without needing a pulpit.

But Charlie Bartlett leaves us with the impression that adults don’t have a clue, so children must make it on their own. If the movie resembled anything close to reality, adult-child role reversal would have been laughable, not laughed at.

Rated R for crude humor, a suggestive sexual situation, brief nudity, and profanity.

Mark believes God made children to desire safe boundaries within the loving care of parents. Deuteronomy 6 sets the standard. Crossroads Bible College students will not be surprised that Dr. Eckel is quoting Deuteronomy . . . again.