Nature knows its name is “creation,” its Author, “Creator.”

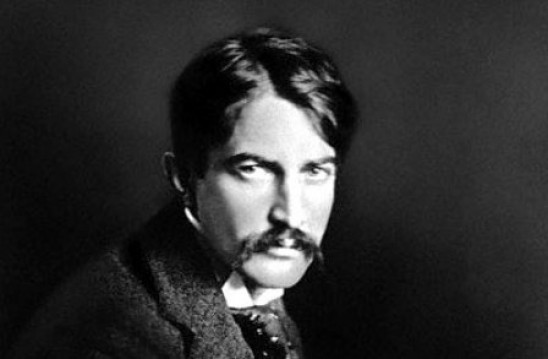

Introduction Stephen Crane would have loved The Matrix. The 1999 film by the Wachowski Brothers hit the Cineplex by storm. Audiences immediately saw its implication: what if there is another reality? The conflict in the film revolves around both saving what is real and convincing others that this “real” exists. Viewers ponder “Am I seeing the world only as I believe it to be or as it really is?” Personal interpretation is crucial. But, does our interpretation create the world or mask something in the world which we refuse to acknowledge? Like The Matrix, Crane is syncretistic, claiming multiple answers to his question. Crane writes about reality as he sees it while carrying on the “eternal debate” (II) about “The Question” (III); both suggest another world. But if Stephen Crane ponders another reality, he does not think it matters.

The problem for viewers of The Matrix and for Stephen Crane is the seeming lack of unity in reality. Some do indeed go through life without questioning “how does everything fit together?” This question, however, is crucial to the whole of life. If there is no organizing principle, if no one is in charge, if humans are left to the whims of fate, and if personified Nature has no master, then we in fact live in Crane’s world. Stephen Crane’s view of life can be summarized as naturalistic cynicism—man against indifferent nature. Crane’s naturalism provides the essential understanding of life; nothing and no one governs Nature. Cynicism is best reflected in Crane’s use of irony. There are no happy endings in Stephen’s writings. The story stops abruptly, not in tragedy, not in triumph, but in timidity. A human writing about humans concludes that existence has no coherence, nothing to hold it together leaving life without meaning. Nature is not against humans; human existence does not matter to Nature. Crane portrays humanity as pathetic, spinning on an apathetic Sphere. If Earth is uninterested in humanity, life is simply a state of flux.

How, then, should a person respond to living in a world of such instability? The Red Badge of Courage is not simply one man’s view of war; the book ultimately ignores the coherence of the universe. If there is no governing structure, order, or framework whereby people interpret life, then everyone is left alone. The verbal shrug of the shoulders—“whatever”—is indeed the answer to every query. Humans by themselves are left to themselves. Crane uses impressionistic realism to make the individual the arbiter and interpreter of truth. Impressionism suggests personal, emotional, visual, situational, and experiential foci. Crane’s reality is created in conjunction with his viewpoint. What he sees, what he feels, is Crane’s outlook. If there is another world behind this world, Crane fashions it for himself and his reader. The clarity of Crane’s assumptions concerning life makes it clear that absolutes do not matter because humans do not matter. There is no past or future to which one would need to give account. The present matters so the individual may interpret his part in unfettered Nature. The root cause of Crane’s approach to literature and thus to life is anchored in rebellion.

Rebellion Against Authority

Crane lived his short life with others who had a long reach. The ideas of Darwin, Nietzsche, and Marx, for instance, had begun to seep into intellectual conversation. Nietzsche’s views were honest: if one rejects the Christian God he must naturally reject the Christian ethic. “Dog-eat-dog” evolutionary theory popularized by Darwin would stream into literary communities. Marx would give the poor a new voice all the while redistributing wealth until the wealth producers were gone. Together with writer friends, Henry James, H.G. Wells, and especially Joseph Conrad, naturalism, atheism, and impressionism were finding inroads into fiction. Nature alone, man alone, and self alone are worldview constructs which discover their voice in Crane.

Seeds of aloneness began to take root in childhood. Stephen Crane grew up in the home of a Methodist minister. Fourteenth in the birth order, it would not be difficult to see that strict discipline along with lack of personal attention could foster individualism. From the beginning Crane rebelled against his father. Baseball, theater, chess, smoking, drinking, and novels—all considered to be vices by Reverend Crane—became Stephen’s focus. Were his dad alive to see, Stephen’s multiple love affairs would also have been a mutiny against religious standards of conduct. Perhaps calling the cannon battery in Red Badge which lobbed shells at the enemy—soon to be destroyed itself—“Methodical idiots! Machine-like fools!” (VI) was really a shot at his dad. Of course, Crane’s father spoke on behalf of the One who ordered the universe. Among the many poems Crane produced, revolt against God was a consistent theme. The Black Riders, while published after The Red Badge of Courage, was concurrent thought as Crane substitutes himself for The Almighty:

A man went before a strange god,

The god of many men, sadly wise.

And the deity thundered loudly,

Fat with rage, and puffing:

“Kneel, mortal, and cringe

And grovel and do homage

To my particularly sublime majesty.

The man fled.

Then the man went to another god,

The god of his inner thoughts.

And this one looked at him

With soft eyes

Lit with infinite comprehension,

And said, ”My poor child!”[1]

It is not surprising that God is left unreferenced in Red Badge. Even a direct argument against the evil of war in the world might have suggested care for God’s existence. So, when one rejects God, one is left by himself. Crane’s anonymous references to “the youth” were statements of aloneness. Crane’s recorded words cement the author’s perspective, “Impressionism was his faith. Impressionism, he said, was truth, and no man could be great who was not an impressionist, for greatness consisted in knowing truth. He said that he did not expect to be great himself, but he hoped to get near the truth.”[2] Left alone with Nature and himself, Impressionism became his god, self became his authority.

Self as Authority

Editors were attracted to Crane’s journalistic impressionism. Stephen began his vocation as a writer in newspapers. While other correspondents recorded events, Stephen took readers to the events through his eyes. “Forget what you think about it and tell how you feel about it”[3] was Crane’s explanation. Reporting became interpreting. Ultimately, Stephen Crane’s journalistic interpretation became the lens in the course of which he wrote his fiction. As Crane’s main character explains, “A certain mothlike quality within him kept him in the vicinity of the battle. He had a great desire to see, and to get news. He wished to know who was winning” (XI). Crane alone possessed an inner knowledge, replacing thinking with feeling. Impressionism is feeling which depends on individual experience and perspective to be the twin arbiters of truth. Impressionistic painters used dots of paint to blur the lines of reality. Crane’s writing created his own reality. Crane questioned all established standards, becoming the sole authority as “the youth” in The Red Badge of Courage.

The youth sees the world around him only through his own eyes. Personal comfort consumed the youth’s focus (I). Experimentation (I) was the basis for his knowledge. With no ultimate reassurance about war outside of himself, he would have to establish his own experience: in one case, “Watch[ing] his legs to discover their merits and faults” (II). Emotion surges through the text as the youth realizes that he cannot understand anyone but himself. “He felt alone in space . . . No one seemed to be wrestling with such a terrific personal problem. He was a mental outcast” (II). Crane’s personal reflection is transferred to the youth who “tried to observe everything” (III). The youth’s omniscient ego enters early and often, “There was but one pair of eyes in the corps” (III). Calling himself “a fine fellow” he seemed supremely gratified that his perspective would carry the day (VI).

The youth called Henry egotistically thinks “his profound and fine senses” (III) are unappreciated by others around him. It is always his “impression” (VI) that matters most. He was a know-it-all (VI). Whether in life or death, the ultimate concern is self; ego reigns. The youth is consumed with envy. Henry’s only concern with others is what they have that he wants. A death-wish is pronounced as he surveys dead bodies littering the battlefield landscape. “He, the enlightened man who looks afar in the dark, had fled because of his superior perceptions and knowledge. He felt a great anger against his comrades. He knew it could be proved that they had been fools” (VII).

Any connection to others is simply to create another opportunity to look in the mirror again. Over and over, the youth calls attention to himself. Consider the youth’s response to impending battle:

He would have liked to have used a tremendous force, he said, throw off himself and become a better. . . . He thought of the magnificent pathos of his dead body. . . . his capacity for self-hate was multiplied. . . . He now conceded it to be impossible that he should ever become a hero. He was a craven loon (XI).

An extended section of chapter 14 identifies the youth’s self-pride. Faith resides in himself. He served his own pomposity, avoiding life’s obligations. While scorning and diminishing his compatriots, he elevated himself. Others’ questions may cause momentary unease, his feelings blown by the wind; but shame is covered quickly. Friend or foe in Red Badge are consistently referenced as inanimate objects or simply animals. The enemy is nothing more than an “unconquerable thing.” When there is a pause for reflection, others’ eyes are on him. On the last page, the reader finds these words, “For he saw that the world was a world for him.” Everything comes back to Henry. Crane’s impressionism was the self-filled chasm between the literary periods of romanticism and modernism. The first reveled in nature, the second used nature. Crane’s passive acquiescence toward Nature created impressionistic realism. The youth’s pride ultimately had little impact. His part in the war proved to be insignificant. “The world was fully interested in other matters” (XVIII).

Nature’s Brute Authority

People may interpret their world but the world has the final word. Crane refers to the world as “Nature.” Capitalization seems to suggest an external authority, a god-like personification. But Crane’s Nature is not a good god. Nature is harsh. Nature is amoral. Nature is indifferent. Nature has no thought for the individual. Humans are interlopers, party-crashers in an uncaring cosmos. Loneliness pervades Red Badge. While there is dialogue aplenty, the reader encounters only the empty echoes of supposed community. Ultimately we are left to ourselves and by ourselves.

Crane expresses surprise at the beginning of his war contemplation. The war had not made an impact on Nature which “had gone tranquilly on with her golden process in the midst of so much devilment” (V) “It seemed now that Nature had no ears. . . . He conceived Nature to be a woman with a deep aversion to tragedy. . . . There was the law, he said. Nature had given him a sign. . . . The youth wended, feeling that Nature was of his mind. She re-enforced his argument with proofs that lived where the sun shone.” (VII) “It seemed that Nature could not be quite ready to kill him” (VIII). “He forgot that he was engaged in combating the universe” (XII). Crane employed his journalistic ability for an article about coalminers in Scranton, Pennsylvania; but his sketch turned into a screed against Nature. “It is war. It is the most savage part of all in the endless battle between man and nature. Man is in the implacable grasp of nature. It has only to tighten slightly, and he is crushed like a bug.”[4]

Crane famously records the war between Nature and humanity in “The Open Boat.” Based on a journalistic entry, Crane had actually endured a shipwreck and used the experience to create the short story. Crane’s correspondent in the boat writes, “When it occurs to a man that nature does not regard him as important, and that she feels she would not maim the universe by disposing of him, he at first wishes to throw bricks at the temple, and he hates deeply the fact that there are no bricks and no temples.”[5] The narrator desires to confront personified Nature “bowed to one knee, and with hands supplicant, saying ‘Yes, but I love myself.’” Nature responds, “A high cold star on a winter’s night is the word he feels that she says to him.” Crane understands the tragedy, the misery of his situation. Life is chance. Human efforts are a shooting star. Both “The Open Boat” and The Red Badge of Courage express outrage against Nature. But there is no recourse for response (“no bricks”) because there is nothing to worship (“no temple”).

Without an absolute authority to reverence, Crane, like the youth and the ship’s journalist, wishes to be his own authority. Yes, Nature is bigger, stronger, and oppressive. But it is no god. Crane rejected The Creator; by so doing, he also rejected the creation. If Nature does not care, then man must return the distain. If they cannot throw bricks at the temple, perhaps humans can heave them at each other.

Presentism as Authority

The War Between The States—heaving bricks at each other—is both backdrop and metaphor in The Red Badge of Courage. Stephen Crane’s novel was an early progenitor of realism—writing as if one were recording events at a local police station. Frank, sometimes graphic prose, made readers feel as if they were there. Decades later other now famous names would add to the tradition: London, Hemingway and Faulkner. It is no surprise Crane wrote in such a manner considering his stints as news reporter. Further, Crane’s lackadaisical attitude toward unfinished schooling created no connections to literary tradition. Crane had no canon. He did not draw from authors’ past work. He wrote in the present. Crane considered his environment to be his “university.” For the prostitute story Maggie it was the Bowery, for “The Open Boat” it was a real-life shipwreck. His human experiences were also unfettered from Heaven’s authority. During the time of Dickens, Conrad, James and Crane, God’s existence was cast in doubt. Until this time, novelists depended upon the authorial-omniscient view—the writer with authority. All voices within the novel are based on the author’s perspective. For Crane, in keeping with his rebellion against authority, he chose variant viewpoints from characters within the script, whether truthful or not.[6] In Crane’s mindset, there is no past, no future, only present influence.

To Crane death is the end of the present. Death anticipated “his eyes burning with the power of a stare into the unknown” (VIII). “He now thought that he wished he was dead. He believed that he envied those men whose bodies lay strewn over the grass of the fields and on the fallen leaves of the forest” (X). Fear of death—“ominously silent he became frightened and imagined terrible fingers that clutched into his brain” (XII)—is ever on Crane’s mind. History becomes nothing more that an individual’s trophy case. But his awards are only meant for him, not future generations. Every person must create their own past and future within the boundary of what Crane calls “present circumstances” (III). Fear is an ever present, present emotion in Red Badge. Crane is not scared of some future event or place like heaven or hell. If there is no fear of afterlife, one must fear losing this life.

If this life is all that matters, fear promotes fulfillment of present desires. The title Red Badge of Courage is embedded within chapter 9. Bravery in battle is reduced to a wound; the youth was envious of other soldiers who had been bloodied. While some commentators focus on the youth’s growth from cowardice to heroism, Henry himself seems to care little if at all. What he wants is a wound, a scar, a mark which confers on him singularity and independence. What strikes the reader is that meaning for the wound is tied directly to here and now. Crane ends his writing with irony—no clarity of dénouement—because the future does not matter. Any purpose, reason, or authority in life is found in this life alone.

No Absolute Authority

Left to ourselves, humanities’ search for meaning is a returned reflection in the mirror. Purpose is self-directed. Belief parties with fate. Emotion is a scream without sound. “The Open Boat” records Crane’s anti-authority assumptions. Speaking of Nature he says:

She did not seem cruel to him then, nor beneficent, nor treacherous, nor wise. But she was indifferent, flatly indifferent. It is, perhaps, plausible that a man in this situation, impressed with the unconcern of the universe, should see the innumerable flaws of his life, and have them taste wickedly in his mind and wish for another chance. A distinction between right and wrong seems absurdly clear to him, then, in this new ignorance of the grave-edge, and he understands that if he were given another opportunity he would mend his conduct and his words, and be better and brighter during an introduction or at a tea.[7]

Crane believes social mores like etiquette are the only authority possible in human terms. The unasked question is “Why obey community standards without absolutes?” If experience is the arbiter of truth, the only possible justification for a standard is having the exact same experience as another. Only then can one claim truth. But individual experience has no universal authority. If no external authority exists, humans are left to the whims of raw power—either in the hands of tyrants or tyrannical Nature. Because Crane’s character makes decisions in the moment, ethics become situational. Community values matter little. What others do or don’t do is unimportant to Crane. The youth is in a state of reaction. There is no anticipation of something better, of a life well lived. People live and then they die. Chance, luck, accident, and coincidence are words marking life’s progress. “Fate” is Crane’s repetitious term of choice throughout Red Badge. “It was as if fate had betrayed the soldier.” (III) Darwin and Nietzsche were accurate: supposed “right” or “wrong” is nothing more than power going to the top dog. It is not as if the youth cares about those around him whether for good or ill. There is an air of carelessness in Henry. Whether something happens or does not happen has no consequence. Self-focus is the youth’s only focus. Crane would agree with William Ernest Henley, “I am the captain of my fate…” Human will is the sole arbiter of choice.

So the reader sees the youth berating his lieutenant who had no appreciation for his fine mind or senses (III). Henry was “the enlightened man” (VII) who knew more than generals (VI). He turns out to be nothing more than a sophomore—a fool who thinks he is wise—expressing full throated pride. Humans create their own knowledge, interpret their own fact, and become their own authority. The last line of Crane’s short story “The Open Boat”summarizes the idea: “the wind brought the sound of the great sea’s voice to the men on the shore, and they felt that they could then be interpreters.”

Conclusion

If others, creation, and The Creator do not matter, love of self is all that is left. Famous novels such as Camus’ The Stranger or Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, or J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye follow the antinomian—anti-authority—perspectives in Crane. Camus’ ethic-less lifeview in novels could not stand real life injustice during World War I. He spoke out against inhuman situations before the United Nations. Jack Kerouac, highly touted as a restless wanderer, ended up back at his mom’s house when needs and rest beckoned. Holden Caulfield exhibits the same hypocrisies he castigates others for in Salinger’s work. The Red Badge of Courage and all likeminded followers leave a void of authority. The emptiness of Crane’s viewpoint is exposed by objectivity, Truth, creation, and reality.

Objectivity and Impressionism Some would argue that the so-called “impressionism” was simply a method of communication. But method and meaning are kissing cousins. A book’s perspective comes out of a point of view, an assumption about life. The audience is consistently given one individual’s sightline in the book. Problems arise, however, when history is interpreted only through one set of eyes. Crane’s dependence on the “seeing” metaphor throughout the novel—possibly 200 references—limits the reader to presentism: the past does not matter and the future is simply dumb luck. Subjectivity is limited to someone’s impression; objectivity is Another’s limitless standard.

Truth and Experience Experience may be a witness to truth but truth does not depend on experience. Henry’s own words demonstrate the ineffectual foundation of experience. “It became impossible for him to invent a tale he felt he could trust” (XI) shows human creativity is limited. “Questionnings made holes in his feelings” (XV) which have the ephemeral nature of fog. What the reader can be sure of is the testimony of R. G. Vosburgh who recorded, “When he was not working he would sit writing his name Stephen Crane, Stephen Crane.”[8] Ego secure, Truth was not. Truth cannot come out of mid-air. Truth needs a transcendent, immutable source outside of human experience.

Creation and Reality People cannot live with the result of their anti-creational beliefs. A Christian vantage point sees a Creator-creation distinction. The separation of first from second means our ultimate concern is “fear Him who can kill both body and soul.”[9] For the unbeliever, emotional fear of the physical world is the only other option. Crane’s viewpoint depends on “under the sun” assumptions.[10] If there is no God, creation is indeed unfettered, untethered, anchorless in the sea Crane so imagined would subsume him.

Reality and Truth While Crane wrote about nature’s indifference and his own malaise about life, still he could not turn away from the plight of the prostitute in Maggie or racism in “The Monster.” Deep within a person resides the template of Another whose Image he sees in other faces. Dallas Willard summaries

Our beliefs are the rails upon which our lives run. We believe something if we are set to act as if it were so. But if our beliefs are false, reality does not adjust to accommodate our errors. A brief but useful characterization of reality is as what you run into when you are wrong—that is, when our corresponding beliefs are not true. Truth is quite merciless; so is reality.[11]

The Matrix and The Red Badge of Courage leave the viewer with two options: continue to live as if another reality does not exist or accept this life as subservient to Another. Rebellion is so much make believe if an Author with Authority exists. Self is but one small word in the universe-filled volumes of One Author. Nature knows its name is “creation,” its Author, “Creator.” Temporal time owes its working to Eternal Authority. And an Author with Authority is Absolute, establishing absolutes. There are two realities; but the natural world is sustained by The Supernatural. Only an Eternal Authority brings coherence with the temporal reality. Stephen Crane’s impression of reality is only the author of “That’s your interpretation.” The Author with Authority is the only Interpreter who matters.

It was a pleasure to write this essay with the help of my son Tyler, whose eagle eye and sensitive spirit sees and hears what my senses never pick up. It was a joy to work with you son. The essay will be published by Integrite: A Journal of Faith and Learning in the Spring, 2013 issue released July, 2013 (https://www.mobap.edu/about-mbu/publications/integrite/). Mark created the Interdisciplinary Studies Program at Crossroads Bible College (2011) and now teaches interdisciplinarity within biblical theology at Capital Bible Seminary.

(Roman numerals–I, II, III–reference chapters in Red Badge.)

[1] Stephen Crane, “The Black Riders,”LI (51).

[2] John Berryman, Stephen Crane: A Critical Biography, rev. ed., (Toronto: McGraw Hill, 1977), 55.

[3] Berryman, Stephen Crane, 25.

[4] Berryman, Stephen Crane, 89.

[5] Stephen Crane, “The Open Boat,” The Red Badge of Courage and Other Writings, ed. Richard Chase, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1960), VI.

[6] John Gardner, The Art of Fiction: Notes on Craft for Young Writers (New York: Knopf, 1984), 157-58.

[7] Stephen Crane, “The Open Boat,” VII.

[8] R.G. Vosburgh, “The Darkest Hour in the Life of Stephen Crane,” in Stephen Crane, ed. Harold Bloom (New York: Infobase Publishing), 36.

[9] Matthew 10:28.

[10] The Bible book Ecclesiastes uses this phrase numerous times emphasizing a naturalistic point of view.

[11] Dallas Willard, “Introduction,” A Place for Truth (Downers Grove: InterVarsity), 16.