A person needs the help of friends in order to act well,

the deeds of the active life

as well as those of the contemplative

A decade has passed since these essays were conceived, yet the ideas continue to mature. Christianity and the Soul of the University should be pondered by all involved with or concerned about Christian higher education. Long standing principles are meant to be pondered and practiced over time. The introduction makes clear that the days of academic fragmentation through disciplinary pride must cease. Interdependence through an interdisciplinary mindset is key to thoughtful, community engagement through all departments at all schools. Community necessitates communication; professors must talk with each other across fields of inquiry.

Communication begins by establishing basic issues and then vital practices, ideas which form two parts of the book. Richard Hays sets the tone of the volume with his expositional overview of 1 John stressing koinonia or fellowship. There can be no division in our commitments since professors are to create intellectual solidarity born of our new birth in Christ. Community is not an idealist’s wish; it is the command of our Lord who made us one. Confession of belief brings with it dedication to work together: “Truth can never be separated from concrete acts of love and mercy” (28). Hays’ five implications for community in the Christian university are not to be missed (35-6). Jesus’ incarnation is the essence of the Christian professor’s distinctiveness.

The distinguishing example is set by John C. Polkinghorne in both his scholarship and interdisciplinarity. Stressing the unity of knowledge as non-negotiable for the believer, Polkinghorne evangelizes with his words

The true university’s quest for interdisciplinary truth may be properly called “Christian,” not because of some imperialist attempt at takeover by the churches, but because those who seek the truth without reserve, whether they know it or not, are ultimately searching for the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ (53).

Polkinghorne pulls no punches—Jesus is the center of the learning universe. Education is not simply an access to knowledge but a development of wisdom. Reason and purpose are central to Polkinghorne’s argument, “Why?” being the most important question anyone can ask. Beauty in math gives example for the claims of interdisciplinary studies. “The indispensability of theology” (61-64) gives the basis for properly interpreting all knowledge accessible because of God’s transcendent unity of all knowledge. “God is the ground of all reality, the integrating factor that ties together the multidimensional richness of human experience” (64).

Joel Carpenter reminds the reader that human experience is much more broad than individual perspectives. “Christian scholars must reorient their course” (66) toward the south and east. Scholarship should seek more practical, more concrete thinking as is the mindset in Asia and Africa. Western models over-departmentalize. “Systematic theology” is rightfully questioned (78-79). Carpenter attacks the assumption of a secularized world (68) suggesting that the East deals with a multiplicity of religious influences. Revision of theories and innovation of approach is needed. Christians have always been at the forefront of educational change when translation endeavors have opened disciplinary doors in other cultures (74). Likeminded Christian professors from far flung locations can “learn new things about the gospel” (84) when a spirit of mutuality is established through curricular synthesis.

But it is David Lyle Jeffrey’s concern for coherence that allows for the basic issue of synthesis. Marking something as “Christian” does not make the discipline Christian. The theatre of study must be in its very essence “Christian” if God creates and sustains all things, if all things are in-and-of-themselves sacred. Indeed, the doctrine of coherence is mentioned consistently throughout the book (75, 78, 86, 94, 122, 161) as a core concern for Christian faculty. Jeffrey’s multiple bullet points (96-98) are worth pondering over and over. In particular, Jeffrey mandates that there be “translators” between disciplines so that departments can talk with each other. The academe needs interdisciplinary bridge builders.

The bridge between theory and praxis is well represented in the book’s second section. Susan Felch says professors should reconsider critiques as student assessments which trigger doubt and distrust. A hermeneutics of delight, on the other hand, prompts one to consider wonder within a Christian context. Literature, humor, and reading highlight the importance of affective objectives highlighted by Felch. Trust makes sense of the world and trumps doubt as a Christian methodology. Aurelie Hagstrom shows another insufficient educational approach—tolerance— in comparison with Christian hospitality considering the university context. “Hospitality is incarnational, morally attuned, and prompted by commitments to truthfulness in word and deed . . . involv[ing] far greater commitments and costs than mere tolerance” (121). Incarnation “requires an affirmation of one’s identity” (129) allowing genuine dialogue to proceed.

Dialogue is not a commitment to vapid views of equality; dialogue necessitates distinctiveness. Steven Harmon pounds the uniqueness of Christian communal conflict as a stake in the ground. Distinguishing the Christian view from others is consistently raised among many authors (35, 36, 87, 119, 125, 175) Harmon rightly identifies the synthetic thread of faith-learning-integration with worship (134). Daniel Russ and Mark L. Sargent petition the reader to think of ways the university can inculcate moral imagination within its curriculum. Committed to language study and the elucidation of the text both authors make stout cases for communication through story, poetry, math, art, and athletics. Christian institutions have developed strong worldview components but their “weakness has been in demonstrating how one lives in a world where worldviews collide” (161). A community, interdisciplinary approach to collegiate teaching would begin to include the redemptive agency the gospel employs. In order to live out true dialogue as Jean Bethke Elshtain desires in chapter two, Daniel Williams’ point in chapter ten is necessary: academic freedom must be premised upon a Christian confession.

A truly Christian university will exhibit its soul, its internal commitments, as it lives its life, its external conduct. Throughout the book authors repeat the essence of incarnation: truth must be embodied (23, 28, 34, 36, 50, 117, 120, 137). A Christian university must provide practicums in every class. “Capstone courses,” if they are believed to be so important, should foundationalize the course of study, not top it off. Internships should be required of all majors; not just 3 hour, 2 month commitments, but 12 hour commitments intermittently or concurrently throughout the program. Team-teaching and dual-department membership should be a staple between divisions. Case studies, novel reading, poetry exercises, labs, expert forums, field trips, and cultural apologetics should be part and parcel of every program design. The affective—the soul—of the Christian university is impacted by acumen as well as action. Belief-being-behavior must become a whole. Thomas Aquinas’ quote, which began the book, is an apt summary of Christianity and the Soul of the University: “A man needs the help of friends in order to act well, the deeds of the active life as well as those of the contemplative” (15).

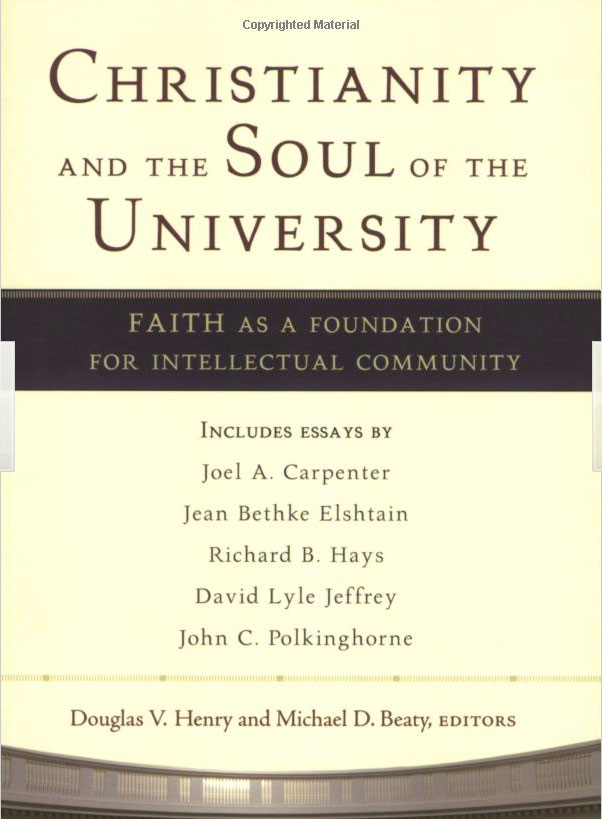

Christianity and the soul of the university: Faith as a foundation for intellectual community. Edited by Douglas V. Henry and Michael D. Beaty. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic. 2006. 192 pp. $6.39. Kindle. Review by Mark Eckel, V.P. Academic Affairs and Director of Interdisciplinary Studies, Crossroads Bible College, Indianapolis, IN. To be published in the Fall, 2013 volume of the Christian Education Journal.

Mark, Thank-you for reminding us of “Christianity and the Soul of the University” and underscoring the countercultural call to interdependence.

How true that

1. “Community necessitates communication; professors must talk with each other across fields of inquiry.”

2. “A man needs the help of friends in order to act well, the deeds of the active life as well as those of the contemplative” (Aquinas).

May God grant us grace to pursue such a vision with Christ followers throughout higher education. To God be the glory!

In Christ, Tom