Humans have a problem. We cannot be trusted.

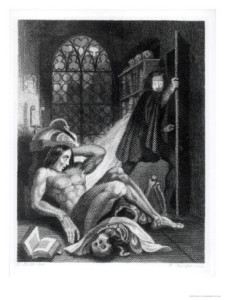

In horror movies, for instance, some sadistic scientist may twist a new application of technology for his own ends. While the audience recoils in terror, we bypass the obvious: the one to fear is the image staring back at us from the mirror. As today’s movies are dependent upon the biblical teaching of inherent corruption, so Mary Shelley consciously or unconsciously depends on the doctrine of depravity to make her point: human corruption issues curiosity for the forbidden leading to the monstrous in Frankenstein.

The reader’s own curiosity is peeked by Shelley’s subtitle for Frankenstein: Or The Modern Prometheus. In Greek mythology, Prometheus was a Titan, stealing fire from the gods giving it to people. Prometheus is portrayed in two different ways in classic literature. To the Greek poet Hesiod, Prometheus was a trickster, a troublemaker. But, to the dramatist Aeschylus, Prometheus was a hero, the champion of humanity, portrayed as such in his play Prometheus Bound.[1] The Prometheus myth inspired Goethe to write a an eponymous poem. Beethoven celebrated heroic self-sacrifice in his symphony “Creatures of Prometheus.” Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Shelley’s husband, constructed “Prometheus Unbound.”

The backdrop to Shelley’s Frankenstein could not be more obvious: doctor and Titan share the same name. But in contrast to the positive offerings from such luminaries as Goethe, Beethoven, and Percy Shelley, Mary’s response to Prometheus was horrific—a term she uses repeatedly in the text. Standing on the outer limits of Enlightenment thinking, Shelley’s generation was seeing, what Paul Johnson calls The Birth of the Modern. Scientists, entrepreneurs, and discoverers of all types were creating new ways to live through invention. Knowledge was accumulated at a breakneck pace: our present information explosion is a direct result. While Dickens rightly lamented the results of The Industrial Revolution in his novels, men creating machines was not to be reversed. Frankenstein was written within the throes of these titanic sociological shifts.

The timeline of Mary’s writing is also important. Frankenstein was written before her husband’s or Goethe’s poetry, much less Beethoven’s Prometheus overture in his 9th symphony. It may be that others responded to her point of view. Mary Shelley wrote within the Romantic time period when the possibility of human perfection was being heralded. Themes from Frankenstein run decidedly against the then current belief that humans are good at heart. Herein is the Rubicon that the Romantics crossed: desire for domination creates autonomous rules, scuttling outside authority. As Nathan Scott said in Religion and Modern Literature Coleridge, Wordsworth, Keats, and Shelley “all make us feel that for them the traditional archetypes and systems of faith had ceased to be effective and that they, as a result, in their dealings with the world were thrown back upon their own private resources.”[2]

Human autonomy is linked with an unusual meteorological event—possibly Promethean fire?—during Shelley’s creativity in 1816. The explosion and planet wide fallout from the volcanic eruption in Tambora, Indonesia created the environmental backdrop for Frankenstein. E. Michael Jones in Monsters from the Id tells the story:

The summer was late in coming in 1816—some might argue that it never came at all—largely because a volcanic eruption in Tambora, Indonesia, spewed tons of ash into the atmosphere, disrupting the climate. Storms abounded. When Shelley, Mary, and Claire had crossed the Alps on their way to Geneva in mid-May, they had needed a carriage drawn by four horses as well as ten men to accompany them and dig them out of the snow drifts. The storms would continue for the rest of the summer and the lightning that accompanied the rain.[3]

The weather reports of that year’s storms highlight what would become the metaphor of life in Frankenstein’s creature: lightening. Electricity allowed curiosity to create the forbidden becoming the monstrous. Prometheus brought fire from heaven to earth. Frankenstein brought life to earth from fire out of heaven.

The volcanic eruption occurred once; but the explosive metaphor rumbles through human history. Shelley uses the warnings given to Walton through Frankenstein to stand as a signpost for the ages: Frankenstein tells Walton in the fourth letter written August 19th,

You seek for knowledge and wisdom, as I once did and I ardently hope that the gratification of your wishes may not be a serpent to sting you, as mine has been. . . . yet when I reflect that you are pursuing the same course . . . I imagine that you may deduce an apt moral from my tale.

Mary Shelley depends on the doctrine of depravity to make her point: our humanity is not perfect nor can it recreate itself. Frankenstein raises the issue of curiosity for the forbidden leading to the monstrous.

If humans are inherently corrupt Shelley would have us consider these questions: How should humanity deal with knowledge? Is imagination a good thing? Did “curiosity kill the cat” or is the cat a cat because it is curious? How far is too far? How important is community or friendship in acting as a constructive critic? What part does adventure or discovery play in the human drama? Questions of knowledge and limitation are recurring concerns in Frankenstein. On the one hand, knowledge is good. It can eliminate disease while producing food. On the other hand, a person full of pride may think he can erect monuments of wonder while constructing his own ethics. Humans bear the mark of modern Prometheus.

Shelley’s own Titan is impassioned to do good. Speaking about his scientific expedition Frankenstein’s friend Walton observes, “You cannot contest the inestimable benefit which I shall confer on all mankind.” On the surface, Walton seems to be a soul desiring to know both the aesthetic qualities of nature and the intricate inner-workings of its order. For example, he is delighted to “feel a cold northern breeze” and is impatient to see “a land surpassing in wonders and beauty.” At the same time he wants to discover the reason a compass works, “the wondrous power which attracts the needle,” and believes he “shall satiate [his] ardent curiosity” with seeing the uninhabited arctic.

But creativity and curiosity, like everything else in a fallen world, is susceptible to misuse and abuse. God declares that devising evil is wrong and those who mistreat their creative talents will be punished.[4] The invention of evil intention always goes against God’s law.[5] Human intellect is capable of hatching evil plots[6], stubbornly refusing Heaven’s admonitions, listening only to its own counsel.[7] Scripture maintains that God is the ultimate “cause,” establishing laws for the beneficence of people, which can be broken by humans, sending adverse consequences.[8]

Listen to Victor Frankenstein’s appetite for science and its possibilities in chapter two:

The world to me was a secret which I desired to divine. Curiosity, earnest research to learn the hidden laws of nature . . . the earliest sensations I remember . . . It was the secrets of heaven and earth that I desired to learn . . . the physical secrets of the world. Natural philosophy is the genius that has regulated my fate . . . I read and studied the wild fancies of Parcelsus and Albertus Magnus with delight; they appeared to me treasures known to few besides myself . . . I had gazed upon the fortifications and impediments that seemed to keep human beings from entering the citadel of nature, and rashly and ignorantly, I had repined [yearned to it].

In lack of community we find lack of accountability. Having no close comrades, Walton resigns, “when I am glowing with the enthusiasm of success, there will be none to participate in my joy.” The explorer refers to this as “a severe evil.” Human interaction is necessary for contentment in accomplishment.[9] God made us for community.[10] Humans function best when working together, sharing joys and sorrows. Accountability grows out of community. Accountability is necessary for confirmation and integrity.[11] But without community, curiosity can become unhinged.

Doctor Frankenstein’s curiosity was excited by the influence of professor Waldman in his first lecture at Ingolstadt. Frankenstein heard of philosophers who have “performed miracles . . . who ascend to the heavens . . . who have acquired new and almost unlimited powers . . . mock the invisible world with its own shadows.” “Such,” he says, “were the words of my fate, enounced to destroy me . . . I will pioneer a new way, explore unknown powers, and unfold to the world the deepest mysteries of creation. . . . The laborers of men of genius, however erroneously directed, scarcely ever fail in ultimately turning to the solid advantage of mankind.” Walton shares the interests of Doctor Frankenstein’s world, what he calls “the passionate enthusiasm for the dangerous mysteries . . . a love for the marvelous.”

But if we have learned anything from creation herself it is this: she belongs to The Creator. When Victor listens to these modern chemists who have, in Waldman’s words, “penetrated into recesses of nature and shown how she works” we should be reminded of Proverbs 8:12-36 where personified wisdom sets order and gives structure to creation. Only He knows the entire, intermeshed workings and purposes of the planet. Humans should explore creation always remembering it is His, the finite beholden to The Infinite. Without this mooring, however, Frankenstein now ascends the staircase toward Waldman’s ephemeral pantheon of superhuman chemists: Victor takes the next step above curiosity to the forbidden.

And this is the problem in The West: we don’t like prohibition. We like to solve problems. We like to know the answer to “why?” Yet, Atul Gawande has said in Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science,

We look for medicine to be an orderly field of knowledge and procedure. But it is not. It is an imperfect science, an enterprise of constantly changing knowledge, uncertain information, fallible individuals, and at the same time lives on the line. There is science in what we do, yes, but also habit, intuition, and sometimes plain old guessing. The gap between what we know and what we aim for persists. And this gap complicates everything we do. . . . What seems most vital and interesting is not how much we in medicine know but how much we don’t—and how we might grapple with that ignorance more wisely.[12]

The 21st century wrestles with exactly the same problems as those of Victor Frankenstein. Human hubris tends to make us scientifically conceited and mystery challenged. Herein is the problem of the forbidden.

So with no respect for prohibition, Victor asked the wrong question in chapter four, “Whence did the principle of life proceed?” Instead, the query should commence with the word, “Whom . . . ?” The so-called elixir of life from which Victor searches foresees an evolutionary concept: that life spawned from primordial soup can be conjured by man. Frankenstein begins from the end: “I became capable of bestowing animation upon lifeless matter.” He describes his own work with these telling phrases, “I tortured the living animal . . . disturbed the tremendous secrets . . . used profane fingers . . . created a workshop of filthy creation . . . did my human nature turn with loathing . . . as if guilty of a crime . . . “

Frankenstein’s sordid practices bear along the cultural climate in which Mary Shelley found herself early in chapter five. Doctor Frankenstein, after confronting the creature in his bedroom, moans, “My heart palpitated in the sickness of fear, and hurried on with irregular steps, not daring to look about me.” Shelley then has him quote Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner:

Like one who, on a lonely road,

Doth walk in fear and dread,

And, having once turned round, walks on,

And turns no more his head;

Because he knows a frightful fiend

Doth close behind him tread.

Could it be that Shelley did not wish to have scientists reading, then practicing, “Frankensteinian” science? Is professional self-censorship important? It should be noticed in modern apocalyptic books (The Island of Dr. Moreau) orfilm (Planet of the Apes) there is a desire on the part of some to keep the secrets of human destruction to themselves so that they are not misused or misapplied. Perhaps, then, Shelley allowed the doctor to recite the warning midway through chapter four, “Learn from me how dangerous is the acquirement of knowledge and how much happier that man is who believes his native town to be the world, then he who aspires to become greater than his nature will allow.”

Here writhes the tentacle, reaching, wrapping around us humans: arrogance. Should we not consider the underlying foundations of Genesis one and two: the origin of anything dictates the ethics of everything? If we view people as only animate, physical objects, will we value them as eternal souls, having life beyond this life? Can the ethics for naturalism or materialism be based on anything beyond the “here and now”? If this life is all there is, will it not be only the powerful who dictate the worth or value of the person? If life is judged based on its quality rather than its sanctity, will we not then only evaluate people based on what they can contribute? And if we heed not Shelley’s warnings, can we live with ethics based solely on individual, community, or government decision?

Answers to these questions teeter on the pinnacle paragraph of Shelley’s work. The monster remarks on Volney’s Ruins of Empires, the apex of the novel in chapter 13:

These wonderful narrations inspired me with strange feelings. Was man, indeed, at once so powerful, so virtuous and magnificent, yet so vicious and base? He appeared at one time a mere scion of the evil principle and at another as all that can be conceived of noble and godlike. To be a great and virtuous man appeared the highest honour that can befall a sensitive being; to be base and vicious, as many on record have been, appeared the lowest degradation, a condition more abject than that of the blind mole or harmless worm. For a long time I could not conceive how one man could go forth to murder his fellow, or even why there were laws and governments; but when I heard details of vice and bloodshed, my wonder ceased and I turned away with disgust and loathing.

Answers to questions concerning ethics, sanctity of life, governmental edicts, and the afterlife are linked directly to our Jekyll and Hyde nature, the divine dignity and human depravity of us all.

Could it have been the aftereffects of the Tambora volcano which provided the setting to expose our true nature in chapter five? “It was on a dreary night of November . . . the rain pattered dismally against the panes . . . it poured from a black and comfortless sky . . .” With this backdrop, Frankenstein describes his creation with the repetitious word “horror”: “I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open . . . this catastrophe . . . by the dim and yellow light of the moon . . . I beheld the wretch—the miserable monster whom I had created . . . the demonical corpse to which I had so miserably given life.”

The word “horror” or its derivatives occur five times in the span of two pages. Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, Golding’s Lord of The Flies, and Marlin Brando’s portrayal in the film Apocalypse Now uttering the unforgettable line, “The horror . . . the horror” continue to call out the end result of our human conceit. The problem is not “out there,” but “in here,” in me. In a manner reminiscent of James “when temptation has conceived, it brings forth sin, which births death,”[13] so Shelley’s warning—curiosity leads to the forbidden leading to the monstrous.

The French word “monster” was a warning of evil. English, Shelley’s lingua franca, expanded the word’s meaning to include “large, misshapen or horrifying creature.”[14] The monster’s size certainly reflects the vocabulary usage of the 19th century British Isles. Frankenstein’s experiment is truly a prodigy: “an extraordinary happening, thought to presage good or evil fortune.”[15] People constantly seek newness. Innovation, we think, moves us closer to answering questions we all ponder. Shelley may have used the word “monster” to analyze the redeeming prospects of science. In the end, however, evil fortune would triumph. Like the insufficiency of leaves for covering[16] human attempts to extricate themselves from trouble bear false hope. Shelley’s monster demonstrates the dictum yet again: only God’s plan is adequate to eliminate the suffering of sin.[17]

The word “evil” lacing Shelley’s book has the connotation of “exceeding due limits” or “extremism”.[18] Surely the author’s intent was to display evil as something that broke established, acceptable boundaries. Shelley seems focused on showing the tragedy, distress, physical and emotional harm that comes as a result of choices which go beyond societal conventions. Scripture casts a different shadow. Evil simply violates God’s commands for people. Evil is anti-God. God’s Word is the objective source of truth for all[19]no matter what humans may decide.[20] Evil is not simply a consequence, but a construct. Evil is set against God. While evil may represent results of decisions made, the essence of evil is a much more important theme.

The famous question “what have I done?” from chapter five produces its first physical consequences of monstrous evil in chapter seven—the death of Frankenstein’s young brother William. The cost in death for Frankenstein would be legion by the end of the book. Though Frankenstein wishes to turn back the clock, overturning the “rash ignorance” he has let loose on the earth, the effects of sin continue. Now that Pandora’s Box was opened, Frankenstein laments his decision to create the monster. Shelley overwhelms the reader with the doctor’s pathos: and well she should. Even though the production cannot be reversed we are left with deep sadness for Frankenstein and a wary mind of our own. The author wisely highlights the destructiveness of humans playing God.

Quoting a verse, Frankenstein recites “Man’s yesterday may ne’er be like his morrow; Nought may endure but mutability.” Shelley identifies the basic problem of all humanity: we are finite, fallen, and fragile. We can create because we bear the mark of our Creator. Yet Shelley seems to reverse the roles. In her book, creature teaches creator. Monster teaches man. Perhaps here we find the perfect mirror. Reading this story we see what we have done: an attempt to usurp the place of God. In the end, Frankenstein observes that “men appear to me as monsters”. We become what we create.

Our culture, on the contrary, has much to learn from Shelley’s teaching on monsters. “The Cookie Monster” is a likeable Sesame Street character. At times parents may even refer to their children as “little monsters”. Presently, we are taught not to “demonize” anyone so as not to ostracize or marginalize people. Even Hollywood’s 2000 release of The Grinch, from Dr. Seuss’ fabled holiday classic, is said to have had a bad childhood: still the Who-villians played a part making the bad Grinch into what he became. In short, 21st century culture has de-mythologized evil.

Yet, monsters do exist. The word “monster” originally meant to warn or divine an omen about evil. Gargoyles on buildings were originally used to alert city dwellers that monsters are everywhere[21]. Frankenstein, Mary Shelley’s masterpiece, addresses multiple, ethical issues, including the belief that humans can create monsters because of our own monstrous, depraved natures.

It is the cry of Frankenstein against Walton’s desire to crack creation’s mysteries early in his letters to which we should give ear. “As I spoke,” Walton intones, “a dark gloom spread over my listener’s countenance . . . tears trickle[d] fast . . . a groan burst from his heaving breast. I paused; at length he spoke, in broken accents: ‘Unhappy man! Do you share my madness? Have you drunk also of the intoxicating draught? Hear me; let me reveal my tale, and you will dash the cup from your lips!’” It is for all to hear, listen, and obey Shelley’s warning—curiosity leads to the forbidden leading to the monstrous.

I propose that the salient, sustaining undertow of Frankenstein’s thinking—the essence of the whole novel itself—is the chapter four admission, “In my education my father had taken the greatest precautions that my mind should be impressed with no supernatural horrors.” Nothing could be more incumbent upon parents and teachers than to instruct our children, our students that there exists a supernatural battle all around us. Fear is appropriate and necessary: but knowing whom to fear is the key.

Frankenstein was the result of a group reading frightful ghost stories and science fiction conversations of what “might be.” Shelley, in her introduction, wanted to “make the reader dread to look round, to curdle the blood, and quicken the beatings of the heart” by writing about the “mysterious fears of our nature and awaken[ing] thrilling horror.” Humans scare easily because terror is real. Sudden movements may frighten us. When the unexpected happens, we scream. But the object of our fear is always something different than what we’re used to. The monster in Frankenstein evokes a response from everyone he meets. Some cower. Others bristle. Many respond with a repugnance, aversion, or loathing. It is the unusual that people respond to—often, negatively.

The monster is fearsome, to be sure. But Frankenstein begs for a solution to fear. The second verse of “Amazing Grace”haunts: “grace has taught my heart to fear, and grace my fears relieved.” It seems that fear is woven throughout our nature. Genesis 3:6-10 records our initial and ongoing response to life. Since the intimate relationship with God was lost at The Fall, we now substitute fear of the unknown for fear of God.[22] We have fear but don’t always seem to know how to handle it. We want to watch horror movies but cover our eyes when the terror strikes. When it comes to God this aphorism is true: we can’t live with Him and we can’t live without Him.

Originally delivered as a much longer address in Dr. Rosalie de Rosset’s “Monsters” class at Moody Bible Institute, Chicago, IL, February, 2009 a version of this essay has now been published in Integrite: A Journal of Faith and Learning, Fall, 2012.

[1]I am not sure how much to make of the fact that the poet regarded Prometheus in a negative light and the actor in a positive one. Could actors, perhaps, have more of a soft spot for rebellion?

[2] Nathan A. Scott, Jr. 1986. “The Name and Nature of our Period-Style,” In Religion and Modern Literature: Essays in Theory and Criticism, ed. G. B. Tennyson and Edward E. Ericson, Jr. (Eerdmans): 129.

[3] E. Michael Jones. 2000. Monsters from the Id: The Rise of Horror in Fiction and Film. (Spence): 69.

[4] Proverbs 3:29; 14:22.

[5] Genesis 6:5; Jeremiah 18:12.

[6] Genesis 8:21; Deuteronomy 31:21.

[7] Jeremiah 3:17; 7:24; 9:14; 11:8; 13:10; 16:12; 18:12; 23:17.

[8] Psalm 33:9; Deuteronomy 30:15; Numbers 32:15; Deuteronomy 28:25.

[9] Ecclesiastes 4:7-12.

[10] Genesis 2:18.

[11] Cf. 2 Corinthians 8:16-21.

[12] Atul Gawande. 2003. Complications: A Surgeon’s Notes on an Imperfect Science. (Macmillan): 7.

[13] James 1:15.

[14] John Ayto. 1990. Dictionary of Word Origins: The Histories of More than 8,000 English Language Words (Arcade): 353.

[15] Webster’s New World Dictionary Third College Edition (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall, 1991): 1073.

[16] Genesis 3:7.

[17] Genesis 3:21; cf. Hebrews 9 and 10.

[18] Dictionary of Word Origins: 210.

[19] Deuteronomy 30:15.

[20] Isaiah 5:20.

[21] Jonah Goldberg. 2000. “In Defense of Monsters.” National Review Online 29 November 2000.

[22] Proverbs 1:7; 9:10.